Exploring 18th-Century Journeys, Justice, and the Human Experience

Imagine: Hoorn in 1756. An seemingly normal day takes a tragic turn when a rye bread baker, Hendrik Baalman (1709-1757), commits a crime that forever changes his life. His subsequent 20 months as a fugitive and eventual capture form the core of Ronald Voortman’s debut novel, ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’ (meaning ‘Flown Soul’). This book isn’t your average fiction; it’s a compelling journey through time, rooted in true events, offering us a unique glimpse into the life of a man on the run in the 18th century.

In this blog post, we’ll delve deeper into the rich themes ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’ has to offer. We’ll explore not only the legal system and criminality of that era, but also the psychological impact of life as a fugitive. What did daily life look like in 18th-century Holland, and what role did migration play in the lives of people like Hendrik? We’ll weigh the balance between historical accuracy and literary freedom, and reflect on the impact of fiction on our understanding of the past. Additionally, we’ll analyze Hendrik’s behavior, the role of memories and reflection, and the meaning of honor and reputation in a small-scale society. Finally, we’ll take a look at the historical sources that made this story possible and the influence of the Enlightenment on the society of that time. Join us on this fascinating journey through history!

Spotlight Insights are like shining a beam of light on a specific point of interest, making it more visible, important, and worthy of closer examination within a broader context. It emphasizes a deliberate and focused attention on a particular element.

Unraveling the Soul of the 18th Century:

A Deeper Dive into 'Uitgevlogen Ziel'

Insights

- From Quakenbrück to Hoorn: The Journey of an 18th-Century Immigrant and His Struggle for a New Existence

- Silver Age, Golden Opportunities? The Daily Life of a Craftsman in 18th-Century Hoorn

- Hendrik Baalman and the Burden of a Good Name: Honor, Shame, and Community in 18th-Century Hoorn

- Hendrik Baalman: The Psychological and Practical Struggle of an 18th-Century Fugitive

- Fate, Choice, and Circumstance: The Elusive Freedom of Hendrik Baalman in the 18th Century

- The Mental Toll of Flight and Imprisonment: A Psychological Dive into the World of Hendrik Baalman

- Crime and Punishment in the Republic: A Dive into 18th-Century Justice

- Between Reason and the Rod: The Enlightenment’s Influence on 18th-Century Justice

- ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’: A Mirror to the Past – The Impact of Historical Fiction

- The Challenges and Ethics of Fiction About True Crimes

- The Puzzle of the Past: Historical Research Behind ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’

Fiction & Facts from the life of Hendrik Baalman (1709-1757)

Get Your Copy: Availability & Details

Explore the availability and full details of

Uitgevlogen Ziel

on our

publication page.

At Donkey Books, we strive to make our stories as accessible as possible. That’s why our titles are available in various formats, so you can always choose what best suits your reading preferences.

From Quakenbrück to Hoorn: The Journey of an 18th-Century Immigrant and His Struggle for a New Existence

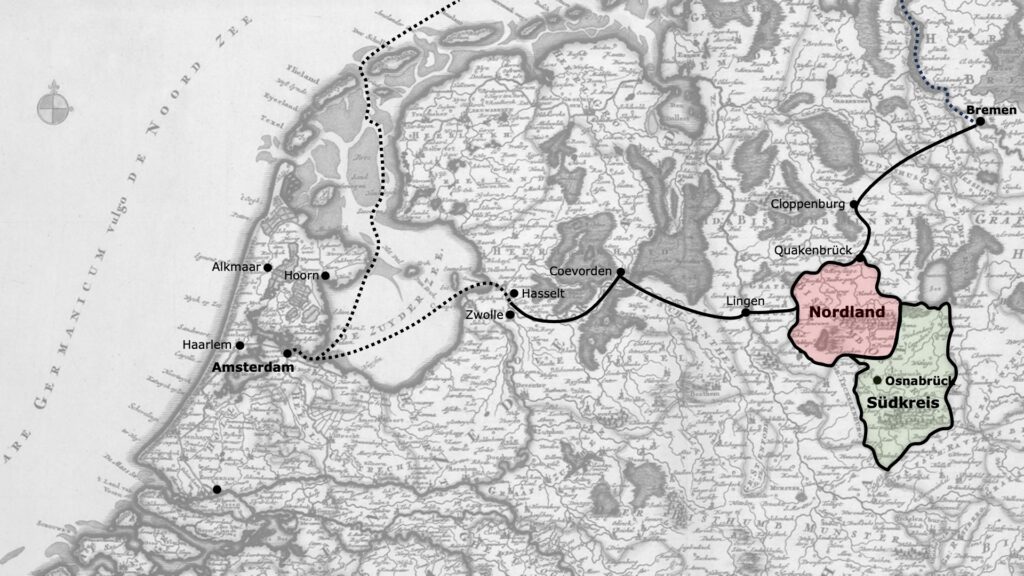

Given Hendrik Baalman’s background as an immigrant from Quakenbrück (diocese of Osnabrück) who came to Holland in 1732, the theme of 18th-century migration and integration is highly relevant. The Dutch Republic had a long tradition of immigrants, although the nature and scale of migration in the 18th century differed somewhat from the Golden Age.

Background of Quakenbrück and Osnabrück

In the 18th century, the diocese of Osnabrück, located in present-day Lower Saxony, was an agricultural area with limited economic opportunities. After the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), the Osnabrücker Nordland experienced significant population growth. Around 1700, this led to a population surplus, putting pressure on the local economy. There was an excess of laborers, but the economy didn’t grow commensurately, resulting in higher unemployment and lower wages. Many people from this region, and from other parts of the German Empire, therefore sought their fortune in the relatively more prosperous (albeit stagnating) Republic.

- 1732 – A Specific Moment: In 1732, the Republic was still an attractive country for migrants, even though the golden times of the 17th century were over. However, there was still demand for labor, particularly in cities, agriculture, and shipping.

- “German” Migration: Many 18th-century immigrants came from the German lands, known as ‘Hoogduitsers’ (High Germans). They often arrived on foot, seeking work and a better life, and found employment in various sectors, from peat cutting and farm labor to crafts, soldiering, and domestic service.

Motives for Migration at the Time (Economic, Social)

Existence of Networks: Migration was often not an individual act. Existing networks of earlier migrants shared information and helped newcomers with their first steps. People often traveled to places where family or fellow villagers already resided.

The motives for migration in the 18th century were complex, a combination of “push” factors (driving people away from their homeland) and “pull” factors (attracting people to the host country).

- Push Factors (from the homeland):

- Economic Necessity: This was by far the main driver. Many areas in Europe faced poverty, famine, low wages, and a lack of arable land. For craftsmen like bakers, there might have been too little work or too much competition in their own region, exacerbated by the aforementioned population surplus in Hendrik’s native area.

- War and Unrest: Although the 18th century was less turbulent than the 17th century, wars and conflicts still caused uncertainty and devastation.

- Lack of Perspective: The absence of future opportunities, both economic and social, in one’s own region.

- Pull Factors (to the Republic):

- Relative Prosperity: Despite economic stagnation, the Republic was still one of the wealthiest and most urbanized areas in Europe, offering more employment and higher wages than most surrounding countries.

- Employment Opportunities: There was a demand for labor, especially in agriculture (peat extraction, land reclamation), shipping (sailors, deckhands), construction, and as domestic servants. Craftsmen like bakers could also earn a living here.

- Tolerance: The Republic was known for its relative religious and cultural tolerance.

How "Foreigners" Were Received and Their Position in Dutch Society

The reception and position of “foreigners” in 18th-century Dutch society was complex and could vary.

- General Attitude: Ambivalence and Pragmatism: There was a pragmatic need for laborers, especially in sectors where the Dutch population itself was less interested (such as heavy manual labor or domestic service). At the same time, there was also mistrust and sometimes xenophobia, particularly during economic downturns or conflicts over employment. Immigrants were often seen as “other” and could become scapegoats for social problems.

- Integration through Work and Marriage:

- Work: The most important way of integration was through work. If someone could practice a profession and support themselves, that was the first step towards acceptance. Hendrik Baalman’s profession as a baker (a valued craft), with a bakery just outside the Oosterpoort of Hoorn, gave him a certain status and demonstrated his initial successful integration.

- Guilds: To work fully as a craftsman, guild membership was often essential. This often required an naturalization procedure and payment of an entrance fee, which could be more difficult or expensive for foreigners. Successful integration often meant adopting the local language and customs.

- Marriage: Marriages with Dutch nationals were an effective way of social integration. Children from mixed marriages were generally considered full Dutch citizens.

- Social Hierarchy and Discrimination:

- Bottom of the Ladder: Many migrants ended up at the bottom of the social ladder, with the heaviest and lowest-paying jobs. This was particularly true for the “Hoogduitsers” who often worked as seasonal laborers or servants.

- Language Barrier: Language (Dutch/Low German) was a significant factor. Migrants who quickly learned the language had a greater chance of success and acceptance.

- Discrimination and Prejudice: Prejudices against immigrants certainly existed. They were sometimes seen as unreliable, poor, or uncivilized. In times of economic recession, tensions could increase.

- Poor Relief: Newcomers without means often had to rely on city poor relief, which carried a stigma.

- Citizenship and Rights:

- Not Automatic: Full citizenship (with political rights) was not automatic and often had to be purchased or earned through years of residency and good behavior. Without citizenship, one could not practice certain professions or use certain facilities.

- Legal System: While the Republic was relatively tolerant, immigrants often found themselves in a more vulnerable position before the legal system. Without deep-rooted social networks or knowledge of the system, they could more easily become victims of abuse or be more severely punished.

Hendrik Baalman’s story can shed interesting light on these dynamics. His ability to become a baker just outside the city of Hoorn indicates a certain degree of successful integration, at least until his crime. His experiences as a fugitive, however, would undoubtedly have cast his status as a “foreigner” in a new light, with his origins perhaps forming an additional obstacle in finding help or evading justice.

Dive Deeper with Spotlight Insights:

Silver Age, Golden Opportunities? The Daily Life of a Craftsman in 18th-Century Hoorn

The 18th century in Holland, often called the ‘Silver Age’, marked a period of relative economic stagnation after the glorious Golden Age. Although the Republic was still prosperous compared to many other European countries, its economic lead diminished. This shift had direct consequences for daily life, even in medium-sized cities like Hoorn, where Hendrik Baalman lived and worked.

Economic and Social Conditions for People like Hendrik Baalman (Baker)

Hendrik Baalman was a baker, a craftsman, and his circumstances were typical for a part of the urban middle class, albeit with nuances.

- Economic Conditions: Economic growth slowed, trade contracted, and industry stagnated after the peaks of the VOC (Dutch East India Company) and WIC (Dutch West India Company) in the 17th century. This led to less prosperity and increased unemployment, especially for the lower social classes. For a baker like Hendrik, price fluctuations of basic goods, particularly grain, were a constant concern. Poor harvests could lead to higher bread prices and social unrest, while good harvests could depress profit margins. Despite guilds’ attempts to limit competition, a baker always had to build and maintain a stable customer base. Setting up and maintaining a bakery required significant capital for ovens, raw materials, and staff. Hendrik was likely not destitute, but not a rich man either; he belonged to the working middle class.

- Strategic Fiscal Advantage: A particular advantage for Hendrik was the location of his bakery. In the city of Hoorn, taxes were levied on goods and services, while outside the city, trade was largely tax-free. Because Hendrik’s bakery was located just outside the Oosterpoort (Eastern Gate) of Hoorn, he was in a unique position. He could offer his bread and other products more cheaply than bakers within the city walls, which gave him a significant competitive advantage. This ensured a constant stream of customers who came out of the city to make their purchases more affordably.

Social Conditions: Society was still highly hierarchical, though less rigid than in some other European countries. A baker like Hendrik belonged to the petty bourgeoisie. For craftsmen, a good reputation and honor were of great importance; an untainted past and reliability were essential for customer trust. Shame or criminality, such as the murder Hendrik committed, could lead to immediate social exclusion and economic ruin. Family life was central; a bakery was often a family business where wife and children worked together. Religion and the community, including neighbors and the church, were important social safety nets, but also sources of social control.

Common Occupations, Crafts, and Guilds in the 18th Century

The 18th-century economy was still heavily dependent on manual labor and crafts.

- Common Occupations: The backbone of the urban economy consisted of craftsmen such as bakers, butchers, shoemakers, and carpenters. In addition, there were merchants and shopkeepers, fishermen and farmers (especially in the vicinity of Hoorn), domestic servants, and a large group of unskilled laborers who held the hardest and lowest-paid jobs.

- Crafts and Their Operation: The traditional hierarchy of master, journeyman, and apprentice was still dominant. A boy started as an apprentice, became a journeyman, and after a “masterpiece” and payment of guild fees, could become a master, after which he was allowed to start his own business. Much production, including baking, took place as home industry in the workshop at home.

- The Guilds: Guilds were crucial corporations of craftsmen. They played an important role in:

- Regulating production: They set quality standards and tried to control prices.

- Economic protection: They protected members against competition from non-members and maintained a monopoly on their craft within the city.

- Training: They organized the training of apprentices and journeymen.

- Social welfare: Guilds functioned as a kind of social safety net for their members (sick, elderly, or widowed members).

- Social control: They upheld professional honor and morals. Misconduct could lead to fines or expulsion. Although their power slowly declined over the course of the 18th century, guilds were still influential.

City and Country Life in that Period

Life in 18th-century Holland was clearly separated between urban centers and the countryside. Hoorn, as a medium-sized city, formed a crossroads of both.

- City Life (Hoorn): Cities were the economic, political, and cultural centers. Hoorn was an important port city on the Zuiderzee, albeit past its golden age. Trade, fishing, and crafts remained important. Cities were densely populated, with narrow streets and houses close together, which brought hygiene problems and diseases. Public life took place in markets and taverns. Despite the density, social control was high; everyone knew each other, which made it extremely difficult for a fugitive like Hendrik Baalman to go unnoticed. Cities had their own governments and courts, and public punishments served as warnings.

- Rural Life (Surroundings of Hoorn): The countryside was primarily agricultural, focused on arable farming and livestock. Villages were smaller and more isolated, often with families who had lived in the same place for generations. Work was hard and seasonal. Although there were also local authorities here, control was less intensive than in the cities, which might offer a fugitive some breathing room, but also fewer means of subsistence. However, there was a constant interaction between city and countryside; farmers brought their products to the city, and city dwellers bought food from the countryside.

The contrast between the ordered, but also controlling city life and the freer, but poorer country life, would have been an important factor in Hendrik Baalman’s decisions and survival during his flight. His earlier advantage as a baker outside the city turned against him after his crime; the familiar location made him extra vulnerable to recognition.

Hendrik Baalman and the Burden of a Good Name: Honor, Shame, and Community in 18th-Century Hoorn

The 18th century in Holland, particularly in cities like Hoorn, was characterized by a small-scale society where social norms and values were closely interwoven with daily life. Anonymity was rare; people knew each other or were aware of each other’s doings. This led to an immense emphasis on honor, shame, and reputation, which dominated the existence of every individual.

Honor: The Foundation of the Individual and the Family

Honor was an extremely valuable possession, for both men and women, and directly reflected on the entire family.

- For Men (and their profession): Male honor was often linked to professional honor, reliability, craftsmanship, and financial stability. A craftsman like baker Hendrik Baalman derived his honor from his competence and his ability to support his family. Adhering to (guild) regulations and delivering good work were essential. Physical resilience and courage also contributed to male honor.

- For Women: Women’s honor was much more strongly connected to their sexual reputation and chastity. An ‘honorable woman’ was chaste, obedient, modest, and rarely moved outside the home. A single misstep could lead to irreparable loss of honor and social exclusion.

Family Honor: An individual scandal or crime directly affected the entire family, potentially hindering marriage prospects or social advancement.

Shame: The Other Side of the Coin

Shame was the direct counterpart of honor and was brought about by deviant behavior, crime, or the violation of social norms.

- Public Punishments: The 18th century saw many public punishments such as flogging, branding, the pillory, or executions. These served not only as a deterrent but also as a public demonstration of shame and a reaffirmation of the social order. A convicted person was literally ‘put on display’ (aan de kaak gesteld) and humiliated before the entire community, maximizing the shame.

- Social Exclusion: Shame inevitably led to social exclusion. People with a ‘bad name’ found it harder to find work, marriage partners, or social acceptance. This was even truer for fugitives like Hendrik Baalman.

Reputation: The Collective Judgment of the Community

Reputation was the collective image the community had of an individual. It was an intangible but extremely valuable asset that took years of honest behavior and hard work to build, but could be shattered in an instant by a crime or scandal.

- “Good Name”: A ‘good name’ was essential for business success, social connections, and even legal matters; testimonies from people with a good reputation carried more weight.

Impact on Hendrik Baalman: As a baker near Hoorn, Hendrik had likely built up a certain reputation. His crime and flight would have completely destroyed this reputation, forcing him to live in anonymity as a fugitive and conceal his past.

The Crucial Role of Community and Neighbors

In the small-scale society of the 18th century, the community and neighbors played a crucial role in maintaining social norms and the functioning of daily life.

- Social Control: Neighbors and community members functioned as informal enforcers of social order. They kept an eye on each other, addressed deviant behavior, and could spread rumors that made or broke someone’s reputation. Gossip and slander were powerful weapons.

- Mutual Help and Support: At the same time, neighbors were often a source of help and support in times of need, illness, or death. They formed each other’s first social safety net.

- Testimony in Court: In the legal system, neighbors often played an important role as witnesses. Their statements about someone’s character and behavior could weigh heavily in a trial.

- The Relationship with Jan Jansz. Schoorl: The relationship between Hendrik Baalman and his former neighbor Jan Jansz. Schoorl is a striking example of this dynamic.

- Witness/Informant: Schoorl may have had information about Hendrik’s behavior or whereabouts. His presence in the story of ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’ on the evening before the execution underlines a deeper connection with Hendrik.

- Representative of the Community: Schoorl represents the ‘eyes and ears’ of the community, someone who embodies the norms and values and is a close witness to Hendrik’s fall. His interaction with Hendrik reflects how the community reacted to crime: with a desire for justice, but perhaps also with a certain degree of curiosity or even human compassion in the final moments.

Morality and the Influence of Religion (Despite the Enlightenment)

Although the 18th century was the ‘Age of Reason’ and the Enlightenment emerged, religion continued to exert significant influence on morality and daily life in the Republic.

- Dominant Role of Christianity: Protestantism (especially the Reformed faith) was the dominant religion and had a strong influence on public morals and legislation.

- Religious Morality: Many social norms were directly derived from religious precepts: honesty, charity, chastity, respect for authority. Crimes were seen not only as violations of the law but also as sins against God.

- Sin and Atonement: The concept of sin, guilt, and the necessity of atonement played a large role. Public confession of guilt and showing remorse were important, both for the individual (to find peace) and for the community (to restore moral order).

- The Rise of the Enlightenment:

- Reason over Dogma: The Enlightenment encouraged the use of reason and questioned traditional authorities, including the church. Ideas of moral self-determination, based on human reason and empathy, emerged.

- Secularization: Although the Enlightenment led to a gradual process of secularization, the majority of the population in the 18th century was still strongly influenced by religious traditions and beliefs.

- Humanity in Criminal Law (Beginning): While torture was still practiced, voices from Enlightenment circles also began to advocate for more humane punishments and fairer trials (think of Cesare Beccaria). These ideas slowly found their way into the legal system.

Influence on Hendrik Baalman: Hendrik’s inner struggle with guilt and remorse, as described in the book, would have been strongly influenced by these religious and moral frameworks. His ultimate acceptance of his fate and the role of a figure like Schoorl in his final hours contain elements of the 18th-century approach to sin and redemption.

Studying these social norms and values offers a deeper insight into the context of Hendrik Baalman’s life and the severity of the consequences of his actions in 18th-century Dutch society.

Hendrik Baalman: The Psychological and Practical Struggle of an 18th-Century Fugitive

The life of an 18th-century fugitive like Hendrik Baalman was anything but idyllic. It was an existence filled with constant threat, loneliness, and a continuous struggle to survive on the margins of society. Ronald Voortman’s ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’ offers a poignant look at this reality, where Hendrik manages to evade justice for 20 months, partly by joining the Admiralty under the pseudonym Jan Klaassen. This deception was brilliant in its simplicity, yet the psychological and practical pressure remained immense. Furthermore, he received help from Jan Harmensz. (c. 1705-after 1756), a crucial detail that underscores the complexity of his flight.

The Psychological Impact: A Life in the Shadows

The constant fear of discovery weighed heavily on a fugitive’s soul. Every unexpected glance, every rumor, or every confrontation could reignite the anxiety of arrest and the severe penalties (corporal punishment, death penalty). This often resulted in sleepless nights and a constant state of heightened alert.

Beyond fear, there was a profound sense of loneliness and isolation. Hendrik Baalman had to leave his familiar life behind: his bakery, his home, and his place in the Hoorn community. His bakery, located just outside the Oosterpoort of Hoorn, was not only his livelihood but also a symbol of his social status and his connection to the local community. Life as a fugitive often meant anonymity, without stable relationships and with a deep-seated suspicion of others. This could lead to painful isolation and a feeling of being cut off from the world.

The loss of identity was another crucial aspect. In the 18th century, your name, profession, and social status were the pillars of your identity. As Jan Klaassen, the anonymous sailor, Hendrik was no longer the respectable baker from Hoorn who had killed a young man with a knife after an argument in a tavern. This loss could lead to inner confusion and an existential crisis, where the continuous act of being someone else posed an enormous psychological burden.

Depending on the nature of the crime and Hendrik’s personality, guilt and remorse likely also played a role. The solitude and lack of distraction provided ample space for reflection on his actions and their impact on victims and loved ones. This could lead to a severe inner struggle.

Finally, the constant need to be on guard could lead to paranoia and mistrust. Everyone, from innkeeper to fellow sailor, could pose a potential threat. Building trust was virtually impossible and dangerous, only intensifying the loneliness.

The Practical Challenges: A Life on the Edge of Existence

The practical life of a fugitive was extremely precarious and required constant adaptation.

- Hiding: Finding places where one could remain inconspicuous was crucial. Large cities offered more anonymity but were also better controlled. Employment with the Admiralty perhaps offered a unique cover; in the bustle of a ship and constant movement, a false identity could be maintained longer. Hiding places ranged from attics to taverns, and changing one’s appearance, for example by growing a beard, could contribute to unrecognizability.

- Means of Subsistence: It was virtually impossible to find legal and open employment, as this required registration or a known identity. Guild membership or obtaining a permit was out of the question. Hendrik’s service with the Admiralty under a false name was an exceptional way to support himself, though the pay was likely meager. Alternatives were often informal odd jobs, day labor, or, out of necessity, petty crime, which further increased the risk of arrest.

- Travel: Traveling without the necessary papers was risky. Although passports were not yet standardized, local authorities (schouts, city councils, soldiers) could easily apprehend and interrogate a fugitive. Less patrolled routes were chosen on foot, by ship, or via dangerous detours. The Admiralty offered unique mobility in this regard; sailing at sea hid Hendrik from land authorities.

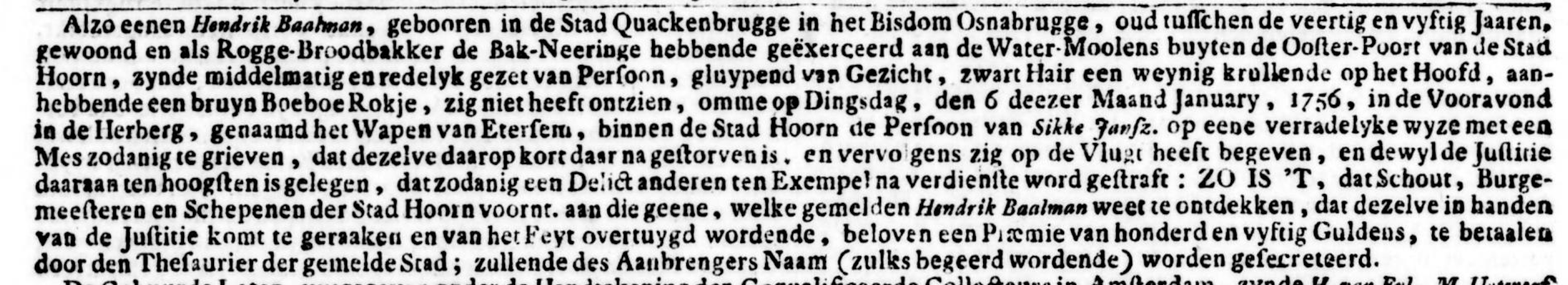

Resource: Oprechte Haerlemsche Courant, Delpher.

The Role of Networks: Help, Betrayal, and the Tragic Revelation

The presence or absence of a network was crucially important for survival. Help from family and friends was extremely dangerous for them, as complicity could be punished. Any support was discreet and sporadic. Organized ‘underground’ networks, as we know them later, did not exist; help depended on individual goodwill or chance encounters.

This is where the role of Jan Harmensz. becomes prominent. His help in Hendrik’s escape from Holland shows that Hendrik was not entirely on his own. This informal support, possibly stemming from a personal bond or shared interest, was life-determining. Such a network offered crucial but vulnerable support in a time without social safety nets. However, it’s important to remember that offering help to a fugitive carried enormous risks for the helper.

The danger of betrayal was constant. Rewards for informing on fugitives were high, and people in poverty or with grudges could easily be tempted to pass on information. This brings us to the possible role of Gerrit Jansz. Ligthart (c. 1730-1785). The fact that Ligthart, also from Hoorn, was on the same ship as Hendrik, who was posing as Jan Klaassen, from September 1756 to January 1757, is telling.

It is plausible that Ligthart recognized Hendrik, given their common origin from Hoorn. This recognition could have led to the crucial identification of Hendrik Baalman as the wanted murderer. Whether Ligthart acted out of opportunism, a sense of civic duty, or perhaps after a confrontation with Hendrik, remains an open question that highlights the complexity of human relationships under pressure. The figure of Jan Jansz. Schoorl, Hendrik’s neighbor who visits him in his cell, possibly contrasts with Ligthart’s role and emphasizes the nuances in human interactions in times of crisis.

The story of Hendrik Baalman and his pseudonym Jan Klaassen, which ultimately seems to have been unraveled by an acquaintance from his past, vividly illustrates the vulnerability of a fugitive existence, even when seeking the shadow of the Admiralty. The role of helpers like Jan Harmensz. on the one hand, and the threat of betrayal on the other, make his escape and eventual capture all the more intriguing.

Fate, Choice, and Circumstance: The Elusive Freedom of Hendrik Baalman in the 18th Century

The life of Hendrik Baalman, as illuminated in “Uitgevlogen Ziel” (meaning ‘Flown Soul’), is a fascinating example of the complex interplay between chance, personal decisions, and external circumstances. In the 18th century, concepts like fate and divine providence were much more deeply intertwined with daily life than in our modern, secular society. The fact that Hendrik managed to evade justice for 20 months testifies to this intriguing interaction.

Hendrik's Own Actions: Cunning and Adaptability

His long period as a fugitive was partly due to his own actions:

- Evasion Skills: Hendrik must have possessed a certain degree of cunning and caution. This included quickly leaving Hoorn, avoiding main roads, maintaining a low profile, and finding temporary shelter and work without raising too many questions.

- Adaptability: The ability to adapt to a life on the margins was essential, possibly by adopting different identities or finding informal jobs.

- Use of Networks: Although risky, he may have initially received help from (distant) family or acquaintances outside Hoorn, which allowed him to bridge the crucial initial period.

- Knowledge of the Land: His background as a baker and immigrant suggests he might have already had travel experience and some familiarity with the routes and conditions in Holland (or the border region).

Coincidences and External Circumstances: Luck or Misfortune?

Besides Hendrik’s own efforts, pure coincidences and external circumstances also played a role in his escape:

- Inefficiency of 18th-Century Policing: Detection methods were significantly more primitive than today. A centralized police force or national databases were lacking; communication was slow. Investigation relied on local schouts (bailiffs), informants, and public proclamations. A fugitive could relatively easily stay under the radar by creating sufficient distance from the crime scene.

- Favorable Circumstances: Sometimes fortuitous events played a role, such as inattention from authorities, a flawed description, or a lack of priority for his case compared to other crimes.

- Inconspicuousness: His ability to remain unnoticed for 20 months can partly be attributed to his own inconspicuous appearance or the fact that he managed to blend in among people who weren’t looking for him.

The Ultimate Capture: An Interplay of Factors

That Hendrik was finally caught after 20 months was also due to a combination of factors:

- A Fatal Mistake: After a long time on the run, fatigue, overconfidence, or a small, fatal error could lead to arrest. This might have been a wrong remark, trusting the wrong person, or returning to an overly familiar environment.

- Betrayal: As discussed earlier, informants (for reward) or people who knew Hendrik and recognized him could have played a role. The role of Gerrit Jansz. Ligthart in the story is illustrative here.

- Increased Search Efforts: Sometimes, as time passed and the case remained unresolved, search efforts were intensified, ultimately leading to his arrest.

- Pure Chance: It could also have been pure chance – a routine check, an unexpected recognition, or a confluence of circumstances beyond his control.

Chance, Decisions, and External Circumstances: The Life Course of Hendrik Baalman

Every individual’s life course is a complex interplay of chance, decisions, and external circumstances, and Hendrik Baalman’s story is a striking example of this.

Chance:

- Place and Time of Birth: It’s pure chance that Hendrik was born in 1709 in the relatively poor Quakenbrück. This ‘fate’ already determined part of his economic and social starting position.

- Encounters: Accidental encounters could have influenced his flight (e.g., finding a place to sleep) or, conversely, his arrest.

- Economic Conditions: The broader economic conditions in the 18th century (such as good or bad harvest years) were largely coincidental for him but had a direct impact on his existence as a baker and his opportunities as a fugitive.

- Circumstances of the Crime: The precise details and cause of the crime itself contain an element of chance, such as a situation that escalated out of control.

Decisions:

- Migration to Holland: This was a conscious and important decision by Hendrik to leave his homeland and build a new life. This choice significantly influenced the rest of his life.

- The Crime Itself: The crime he committed was (likely) a conscious act, or at least a decision that led to his actions, with catastrophic consequences.

- The Decision to Flee: Instead of surrendering, Hendrik chose to flee, which turned his entire existence upside down and made him a fugitive.

- Choices During Flight: Every day as a fugitive was filled with decisions: where do I sleep, what do I eat, whom do I trust? These micro-decisions partly determined his survival.

- Reaction in the Cell: His behavior and any confession in the cell were also decisions (whether forced or not).

External Circumstances:

- The Political and Social Structure of the Republic: The decentralized legal system, the guild structure, and the social norms and values (honor, shame) were external circumstances that profoundly influenced his life and the consequences of his actions.

- The State of the Economy: The general economic stagnation of the 18th century in Holland may have affected his opportunities as a baker and as a fugitive.

- Weather Conditions: For someone traveling on foot or with rudimentary transport, weather conditions could have a major impact on their ability to travel and find shelter.

- The Actions of Others: The decisions and actions of authorities, witnesses, or potential betrayers were external circumstances crucial to his capture.

The story of Hendrik Baalman in “Uitgevlogen Ziel” provides insight into these complex interactions. This makes the story not only historically interesting but also universally relatable.

The Mental Toll of Flight and Imprisonment: A Psychological Dive into the World of Hendrik Baalman

The story of Hendrik Baalman in “Uitgevlogen Ziel” offers a profound insight into the human psyche under extreme pressure. As a fugitive and later a prisoner, Hendrik undergoes a wide range of psychological states and behaviors that are universal to people in crisis situations.

The Psychology of a Fugitive: 20 Months on the Run

During his 20-month flight, Hendrik’s inner world would have been characterized by:

- Survival Instinct: The primary drive was undoubtedly survival. This manifested in constant alertness, avoiding familiar places and people, and finding ways to obtain food and shelter.

- Paranoia and Mistrust: The continuous fear of discovery would lead to deep mistrust of almost everyone. Strangers were potential betrayers; even acquaintances could be dangerous. This could result in social isolation and the avoidance of deep connections.

- Adaptability: Some fugitives develop remarkable adaptability. Hendrik would likely have quickly learned new skills (e.g., as a sailor), adapted to unusual living conditions, and developed a certain ‘street smarts’.

- Identity Change: By adopting a different identity (Jan Klaassen) to conceal his true self, Hendrik could experience a sense of self-estrangement.

- Physical and Mental Exhaustion: The constant stress, irregular nutrition, sleep deprivation, and the physical demands of travel could lead to extreme exhaustion, which would affect his judgment and emotional stability.

- Hope and Despair: Periods of hope (when he felt safe for a moment or found a place) were likely interspersed with deep despair about his bleak future, such as the moment he learned of his wanted notice in the newspaper.

- Rationalization/Denial: To cope with guilt, people sometimes try to rationalize their actions or deny their severity.

The Psychology of Imprisonment: Life in the Gevangenpoort

Once in the cell, in the Gevangenpoort (Prison Gate), Hendrik’s psyche undergoes another transformation:

- Shock and Acceptance: The initial phase after arrest can be shock, followed by a slow acceptance of the new, limited reality.

- Deprivation: 18th-century prisons were places of deprivation – of freedom, privacy, contact with the outside world, and often basic comfort. This could lead to lethargy, depression, or agitation.

- Expectation of Punishment: The fear of impending punishment, especially if the death penalty loomed, would have been overwhelming. This could lead to pleading, negotiating, or resignation.

- Interrogation Techniques and Confession: 18th-century interrogation techniques, including the threat of torture, were aimed at forcing a confession. The psychological pressure could be so immense that a suspect eventually confessed, even if innocent. Hendrik immediately confessed his crime, but sources indicate he hoped for some degree of forgiveness to avoid the harshest penalty.

- Reflection and Regret: The forced inactivity and isolation in the cell offered (un)willing space for reflection on life, the crime, and the choices made. This could lead to profound regret and remorse.

Dealing with Extreme Pressure, Guilt, and Remorse

Hendrik Baalman’s story illuminates universal human experiences related to extreme pressure, guilt, and remorse:

Extreme Pressure:

- Fight, Flight, or Freeze: The primal instincts of fight, flight, or freeze manifest. Hendrik’s flight behavior is a clear ‘flight’ mechanism. In the cell, ‘freeze’ or ‘fight’ (by offering resistance, often futile) could be the reaction.

- Coping Mechanisms: People often develop coping mechanisms, such as dissociation (mental detachment), fantasy, hope for a miracle, or minimizing the severity of the situation.

- Decline in Cognitive Functions: Chronic stress can lead to impaired concentration, memory problems, and difficulty making decisions.

Guilt and Remorse:

- Guilt versus Remorse: Psychologically, guilt is often related to a specific act (“I did something wrong”), while remorse is a deeper, more existential feeling of regret about who you have become or the harm you have caused (“I have become a bad person because of what I did”). Guilt can motivate restitution or penance; remorse can be paralyzing.

- Different Reactions: Some people are consumed by guilt and remorse, others try to suppress or deny it, or shift the blame to others. The societal context also played a role here: religion often offered paths to atonement and forgiveness.

- The Role of Punishment: In the 18th century, punishment was often aimed at atonement and the recognition of guilt (confession). Public humiliation was also intended to enforce guilt.

Memories and Reflection: The Crucial Role of Conversations with Jan Jansz. Schoorl

The interaction with Jan Jansz. Schoorl, his former neighbor, on the last evening before the execution of the sentence, is a crucial literary and psychological element:

- Memories as a Coping Mechanism: In a situation of extreme stress and impending death, memories can offer an escape from harsh reality. They can also serve to reconstruct one’s own story and give meaning to a life that is about to end.

- Reflection and Self-Analysis: The conversations with Schoorl offer Hendrik a chance to reflect on his life: his youth in Quakenbrück, his journey to Holland, his life as a baker near Hoorn, the circumstances that led to the crime, and his time as a fugitive. This could be an attempt to understand his actions, justify himself, or gain a deeper insight into his mistakes.

- The Role of the “Listener”: Jan Jansz. Schoorl acts as a listener, perhaps even a kind of confessor. The presence of someone who listens to your story, especially in such an isolated and final setting, is psychologically invaluable. It can help the fugitive regain his identity and feel seen before he vanishes.

- Seeking Answers/Forgiveness: Schoorl’s motivation to get answers (why did Hendrik do what he did?) is also important. This could be an attempt to help the community or himself process the crime. The deeper emotion of these conversations also concerns forgiveness – self-forgiveness, forgiveness from others, or forgiveness by a higher power.

- The Truth and Fiction of Memories: Memories are subjective and can be distorted by trauma, guilt, or the desire to view the past in a certain light. In the fictional narrative, the author has utilized the facts as much as possible to convey Hendrik’s psychological depth.

This deepening of the human psyche in times of crisis adds a richer dimension to Hendrik Baalman’s story.

Crime and Punishment in the Republic: A Dive into 18th-Century Justice

The 18th century in the Dutch Republic (Republic of the Seven United Netherlands) was a period of transition, including in the realm of justice and criminality. While the Enlightenment brought new ideas about more humane punishments and a fairer legal system, many practices were still rooted in older traditions

The Legal System in the Dutch Republic in the 18th Century

The Republic did not have a central, uniform legal system as we know it today. Justice was highly decentralized and varied by province (gewest) and even by city. Each province had its own courts, and within those, there were different levels of jurisdiction:

- Local Jurisdiction (lage jurisdictie): These were often the schepenbanken (aldermen’s benches) in cities and villages, which dealt with minor civil cases and less serious crimes. They consisted of mayors and aldermen (lay judges).

- Urban Courts (hoge jurisdictie): Larger cities had courts that also had jurisdiction over “corporal punishment” (criminal) cases, meaning crimes subject to severe penalties.

- Courts of Justice (Hoven van Justitie): Above the local and urban courts were the Courts of Justice for each province, such as the Court of Holland and Zeeland in The Hague. These were the highest appeal instances and also handled more serious crimes.

- No Strict Separation of Powers: Importantly, there was no strict separation between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The same institutions could have both administrative and judicial tasks. Judges often had significant discretionary power, which could lead to arbitrariness.

Interrogations and Sentences:

- Secret and Written: The criminal process was largely secret and written. The accused had almost no rights and often no access to legal assistance.

- Torture (pijnbank): Well into the 18th century, torture, known as “sharp examination” (scherpe examinatie) or the rack (pijnbank), was a common means of extracting confessions. A confession was often essential for a conviction. There was a rule that a confession made under torture had to be repeated later in court, so that the accused could not claim they only confessed due to pain. Nevertheless, the threat and psychological pressure were immense.

- Evidence and Witnesses: Besides confessions, witness statements and material evidence were also collected, although their interpretation could differ from today’s.

- Sentences: Sentences were often pronounced and carried out in public to create a deterrent effect. Punishments were diverse and could range from fines and banishment to corporal punishments and the death penalty.

The Role of the Gevangenpoort:

The Gevangenpoort (Prison Gate, and similar city gates or buildings that served as prisons) in the 18th century was primarily a place of pre-trial detention. Suspects were held here awaiting their trial and sentence.

- No Imprisonment as Main Punishment: Confinement as a punishment in itself (i.e., imprisonment as we know it) was still relatively rare and only emerged later in the 17th and 18th centuries, primarily in tuchthuizen (houses of correction) for beggars, vagrants, and petty criminals, with the aim of “instilling discipline.”

- Varying Conditions: Conditions in the Gevangenpoort varied greatly. The wealthy could often pay for a better, more spacious cell (such as the “Knight’s Chamber” in the Gevangenpoort in The Hague), while poorer prisoners sometimes were confined with many others in small, unhygienic spaces.

- Torture Chamber: Many Gevangenpoorten also housed torture chambers where the “sharp examination” was conducted.

- Symbolism: The Gevangenpoort was not only a practical space but also a symbol of government authority and justice.

What Types of Crimes Were Common and How Were They Punished?

The 18th century saw a wide range of crimes, from minor offenses to serious felonies. Punishments were often public and cruel, intended to deter and maintain public order.

Common Crimes:

- Theft: This was by far the most common crime. It often involved the theft of agricultural products (grain, livestock), clothing (valuable at the time), or household goods. Grand theft (e.g., with violence or burglary) could lead to very severe penalties.

- Violent Crimes: Homicide, murder (often more severely punished than manslaughter due to its “secret” nature), assault, and disturbing public order.

- Sexual Offenses: Rape, adultery (could lead to shame and social exclusion), sodomy (homosexuality, very strictly punished).

- Forgery and Fraud: In a society where identity and reputation were important, fraud, for example with false identity papers, was a serious offense.

- Riot and Rebellion: Resisting authority, unlawful assembly, and rioting were severely suppressed.

- Minor Offenses: Begging, vagrancy, drunkenness, prostitution (though sometimes tolerated, also punished).

Punishments: Punishments were often physical and humiliating:

- Death Penalties:

- Hanging: Most common death penalty for severe crimes, often in a public place. It was also a dishonoring punishment.

- Beheading: For more severe crimes, sometimes considered a “nobler” punishment for persons of higher standing.

- Breaking on the Wheel: A gruesome punishment where the condemned’s limbs were broken with a wheel, often prior to death.

- Burning, Drowning, Strangulation: Less common, but applied for specific crimes (e.g., witchcraft, infanticide).

- Corporal Punishments:

- Flogging: Public lashings on bare skin, often at the pillory.

- Branding: A mark (often a letter or a coat of arms) was branded with a hot iron on the shoulder or back, as a permanent visible criminal record.

- Mutilation: Amputation of hands (for theft), ears, noses, or tongues, although this was less common in the 18th century than in earlier centuries.

- Dishonoring Punishments (Public Shame Penalties):

- Pillory (Aan de kaak/schandpaal): Convicts were publicly displayed, sometimes with a sign around their neck stating their crime. They could be pelted and mocked by the public.

- Sitting in the Shame Cloak/Chair (Schandmantel/schandstoel): Similar humiliation.

- Dragging a Shame Sled (Schandslede): A convict had to pull a sled, loaded with stones or sand, through the streets.

- Financial Penalties:

- Fines: For lighter offenses, or as an addition to other punishments.

- Confiscation of Goods: Seizure of the condemned’s possessions.

- Custodial Sentences (still limited):

- Banishment: The condemned had to leave the city, province, or even the Republic and were not allowed to return under penalty of heavier punishment. This was a common penalty.

- Galley Sentence: Convicts were sent to galleys as rowers (mainly in Mediterranean countries, less in the Republic).

- Houses of Correction (Tuchthuizen): For “troublesome” individuals such as beggars, vagrants, and prostitutes, intended for re-education through labor.

The Social Consequences of Criminality for an Individual and Their Environment

Criminality in the 18th century had far-reaching social consequences, both for the perpetrator and their immediate surroundings.

- For the Individual:

- Shame and Loss of Honor: In a time when honor and reputation were of great importance, a conviction (especially a public punishment) meant immense shame. This was not only for the perpetrator but also for their family.

- Social Exclusion: Convicts, especially after severe punishments or banishment, were often cast out by the community. It was difficult to find work, a place to live, or even to maintain social contacts. Branding made the “punishment” permanently visible.

- Economic Ruin: Confiscation of goods, high fines, and loss of work could lead to poverty for the perpetrator and their family.

- Trauma and Psychological Impact: The confrontation with the harsh legal system, interrogations (with or without torture), the uncertainty of the verdict, and public humiliation must have exacted an enormous psychological toll.

- Recidivism: For some, social exclusion and poverty led to a vicious cycle of criminality, joining gangs or leading a wandering existence.

- For the Environment (Family and Community):

- Shame and Stigma: The family of a convicted person often shared in the shame. This could affect marriage prospects, economic outlook, and social acceptance.

- Economic Disruption: If the main breadwinner was punished or banished, the family could fall into deep poverty.

- Fear and Insecurity: Criminality, especially violent crime, caused fear and insecurity within the community. Public punishments were precisely intended to address this feeling and deter.

- Disrupted Social Cohesion: Especially in smaller communities, criminality could disrupt social bonds and lead to mistrust.

- Role of Neighbors and Acquaintances: Neighbors and acquaintances often played a role in the process, as witnesses or sometimes as informants. This could strain relationships.

The 18th-century legal system was thus a complex whole, with local variations and a mix of traditional and emerging Enlightenment ideas. For Hendrik Baalman, whose story unfolds in this context, the social consequences of his crime and flight must have been overwhelming. His story is a mirror reflecting the harsh reality of justice and injustice in that era.

Between Reason and the Rod: The Enlightenment's Influence on 18th-Century Justice

Although Hendrik Baalman, an 18th-century baker, was likely no philosopher or Enlightenment thinker, his life unfolded during a period of profound intellectual and societal changes. The echoes of these shifts resonated through daily life and even the legal system. The 18th century is known as the ‘Age of Enlightenment,’ a time when reason, critical thinking, and a belief in human progress took center stage. Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Locke (whose ideas significantly influenced the Netherlands) criticized traditional authorities like absolute monarchy and the church, advocating for:

- Rationality and Science: Knowledge, they believed, should be gained through observation and logical thinking, not through dogma or tradition.

- Freedom: Freedom of thought, expression, and belief (tolerance) were core values. The concept of individual liberty gained ground.

- Equality: The Enlightenment criticized the rigid class system and advocated for greater equality, based on the idea that every human is born a ‘tabula rasa’ (blank slate) and acquires knowledge and experience.

- Malleability of Society: There was a belief that society could and should be improved through reforms, aiming for the happiness of all.

- Secularization: While many Enlightenment thinkers were not anti-religious, they did advocate for a separation of church and state and a more personal approach to faith, detached from dogmatic ecclesiastical tenets.

Traces of New Ideas: Justice, Humanity, and Individual Freedom

Although radical changes often weren’t fully implemented until the late 18th and 19th centuries (consider the Batavian Revolution and the French Revolution), Enlightenment ideas did permeate society and the legal system throughout the 18th century, albeit gradually and with regional differences.

- Justice and Humanization of Criminal Law:

- Criticism of Arbitrariness: Enlightenment thinkers criticized the arbitrariness in the Ancien Régime‘s legal system, where punishments often depended on the perpetrator’s social status or judicial whim. A call for equality before the law emerged, meaning everyone should be tried in the same manner, regardless of origin.

- Criticism of Cruel Punishments: The Italian Enlightenment philosopher Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) published his influential work Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments) in 1764. In it, he advocated for:

- Proportionality: Punishments should be proportionate to the severity of the crime.

- Abolition of Torture: Torture (tortuur) was increasingly criticized in the 18th century as inhumane and unreliable (people would confess to anything to stop the pain). Although ‘sharp examination’ was still practiced in 1756 (Hendrik Baalman’s case), cities and provinces in the Republic gradually began to abolish or limit its use in the second half of the 18th century. This demonstrates the Enlightenment’s influence.

- Abolition of the Death Penalty: Beccaria argued for the abolition of the death penalty, except in exceptional cases of state danger. He preferred imprisonment and forced labor as more effective and humane punishments. While the death penalty was still widely applied in Hendrik’s time, this criticism marked the beginning of a slow shift.

- Publicity of Justice: There was a growing awareness that justice should be transparent and public, as a check on judges.

- Individual Liberty:

- Criticism of Absolute Power: The Enlightenment challenged the power of monarchs and nobility, advocating for more rights and participation for citizens. Although the Republic did not have an absolute monarchy, it did have an oligarchy of regents. Enlightenment ideas encouraged critical thinking and self-development.

- Self-determination: The idea that humans were responsible for their own happiness or misfortune, rather than God, gained traction. This strengthened the concept of individual autonomy.

- Religious Tolerance: While a certain degree of tolerance already existed in the Republic, the Enlightenment reinforced the idea that everyone had the right to their own faith and that religious beliefs were personal.

- Impact on Hendrik Baalman’s Case:

- Torture: The question of whether Hendrik was tortured to extract his confession is crucial. If he confessed after “sharp examination,” this stands in stark contrast to Enlightenment ideals, but it was still a common practice. However, discussion about this practice was well underway, paving the way for later reforms.

- Legal Procedure: Although the 18th-century legal process was still largely written and secret, and the accused had few rights, the first cracks in this system began to appear.

- Public Opinion: Even if legislation wasn’t yet fully enlightened, public opinion (influenced by Enlightenment ideas) could affect how a criminal and their punishment were viewed. Was there more room for compassion, or did the call to set an example remain dominant?

- The Role of the Magistrate: The judges and magistrates who convicted Hendrik Baalman may have themselves been influenced by Enlightenment ideas, or were pressured by intellectual currents calling for more humane justice. The way they formulated their verdict, or the extent of their ‘discretionary’ space, could already show signs of this influence.

Hendrik Baalman’s story, even as a ‘common’ man, can thus form a microcosm of the broader societal and intellectual changes of the 18th century. It demonstrates how grand ideas slowly permeated daily life and how society dealt with crime and justice. His trial and conviction occurred at the intersection of an old, often cruel legal system and the emerging, more humane ideals of the Enlightenment.

'Uitgevlogen Ziel': A Mirror to the Past – The Impact of Historical Fiction

“Uitgevlogen Ziel” (Flown Soul) by Ronald Voortman is a fascinating example of how historical fiction combines facts and fabrication to tell a captivating story about the past. The book deftly navigates the line between remaining true to historical reality and the necessity of a compelling narrative.

Historical Accuracy: The Foundation of the Story

The strength of historical fiction lies in the extent to which it provides an accurate representation of the time and events. In “Uitgevlogen Ziel,” historical accuracy forms the framework within which the story unfolds:

- Factual Data: The core of the story rests on demonstrable facts, such as Hendrik Baalman’s name, his birth and death dates, the location Hoorn, the year of the crime (1756), the nature of the crime, his 20-month period of flight, and his eventual conviction.

- Historical Context: The author conducted extensive archival research to accurately portray 18th-century society. This includes daily life, professions, guilds, the legal system, social norms, architecture, clothing, and even linguistic usage. This ensures the reader is immersed in a credible world.

- Historical Details: Even seemingly minor details, such as the names of those involved (magistrates, witnesses) and specific locations (streets, taverns), are historically accurate, contributing to the authenticity.

Literary License: Filling in the Gaps

While facts form the backbone of the story, literary license offers the opportunity to bring the past to life and add depth:

- Filling in Gaps: Historical sources are rarely complete. The author uses literary license to fill in the gaps with believable details about Hendrik’s thoughts, feelings, conversations, and motivations, always within the realistic parameters of the time.

- Storyline and Plot: The chronology of events is accurate, but the author skillfully interweaves this with memories and flashbacks. This prevents the story from becoming a dry enumeration of facts, allowing events to gain meaning at the right moment. Incidents can be emphasized or toned down, which doesn’t necessarily have to align with Hendrik’s own experiences.

- Character Development: Beyond Hendrik Baalman’s factual actions, the author elaborates on his inner life. His struggle with guilt, fear, hope, and despair makes him a three-dimensional and empathetic character.

- Thematic Deepening: Through the fictional elements, the book delves deeper into universal themes such as justice, morality, survival, and identity. The historical facts serve as a framework for these deeper layers.

The combination of these elements means the reader understands that, while the broad strokes and historical context are correct, many of the details (dialogue, specific emotions, internal conflicts) have been filled in by the author. “Uitgevlogen Ziel” is inspired by the facts, not a literal report of them.

The Challenges and Ethics of Fiction About True Crimes

Writing about true crimes, even those from long ago as in “Uitgevlogen Ziel,” involves specific ethical considerations:

- Respect for Victims and Next of Kin: This is the most crucial ethical consideration. Although Hendrik Baalman’s crime occurred centuries ago and there are no direct descendants, the principle of respect remains vital. The fiction focuses on Hendrik Baalman’s experience, while the factual section also sheds light on the victim’s perspective.

- Historical Interpretation versus Sensationalism: The author has tried to provide an accurate and nuanced representation of the crime and its consequences, without sensationalizing or romanticizing it. This avoids the exploitation of human suffering.

- Accuracy of the Crime Itself: The crime is described as detailed and accurate as possible, based on the available facts. Legal processes, witness statements, and verdicts are correctly presented.

- Perpetrator’s Motivation: While it can be tempting to psychologize a perpetrator’s motivation, the fiction has remained as close as possible to the known facts. There are no ‘invented’ motivations, and the perpetrator is neither unnecessarily ‘understandable’ or ‘sympathetic’, nor is he depicted judgmentally.

- Potential Influence on Public Opinion: Even after centuries, a popular historical novel can influence public perception of events and those involved. The author has taken responsibility not to spread deliberate misinformation.

- Transparency About Sources: The author is transparent about the sources used and where the fiction begins. The factual section includes source references, allowing readers to verify what is true and what is fictional, and even offering opportunities for their own research.

The Impact of Fiction on Our Understanding of the Past

Historical fiction has a significant impact on how the general public experiences and understands the past:

- Accessibility and Empathy: Historical fiction makes the past more vivid than dry history books. By identifying with characters, readers can develop empathy for people from other times. Hendrik’s story helps us imagine what it was like to live in 18th-century Holland, including the challenges of migration and justice.

- The “Feel” of the Time: History books present facts, but fiction can convey the ‘feel’ of an era: the atmosphere, smells, sounds, fears, and hopes of people. This contributes to a richer historical imagination.

- Awareness of Lesser-Known Histories: Stories about ‘ordinary’ people like Hendrik Baalman, whose lives rarely make it into major history books, can be brought to light through fiction. This broadens our understanding of the inhabitants of the past.

- Risk of Misinformation: The greatest danger is that fiction can distort historical facts or create myths that are difficult to debunk. By combining facts with fiction, “Uitgevlogen Ziel” significantly minimizes this risk.

- Debate and Discussion: Historical fiction can give rise to important debates about historical interpretation, ethics, and the nature of historiography.

The Puzzle of the Past: Historical Research Behind ‘Uitgevlogen Ziel’

If you’re fascinated by history and want to understand how historical fiction like “Uitgevlogen Ziel” comes into being, then insight into historical research and source usage is essential. The story of Hendrik Baalman, an ‘ordinary’ 18th-century man who, through his crime, ended up in the archives, is a perfect example of how you can reconstruct the past.

The author of “Uitgevlogen Ziel” consulted various primary and secondary sources, all mentioned in the book. Precisely because Hendrik was an immigrant and committed a crime, the most fruitful information is found in judicial and administrative archives. Let’s look at which sources you yourself could consult if you want to follow in Hendrik’s footsteps!

Diving into Judicial Archives: The Core of the Story

Judicial archives are goldmines for research into crimes and their perpetrators in the 18th century. Here you’ll find the hard facts:

- Criminal Sentence Books (Vonnissen): These contain the final judgments of the court. For a case in Hoorn, you could find these in the archives of the city of Hoorn or the Court of Holland (Hof van Holland). A sentence often states the name of the convicted person, the nature of the crime, the date, and the imposed punishment. This is the absolute core of Hendrik’s story.

- Interrogation Records (if preserved): These are the minutes of the interrogations of the suspect and witnesses. They are invaluable for reconstructing the events, the suspect’s statements (and his possible motives as he presented them), and the names of those involved.

- Confession Books: These are specific books in which suspects’ confessions were recorded, often under oath and sometimes after ‘sharp examination’ (torture). These provide direct, albeit sometimes forced, insight into the perpetrator.

- Publications of Sentences/Placards: Sentences were previously made public via printed placards or proclamations to serve as a deterrent. Here you can often find detailed information about the person and the crime.

- Accounts of Justice (Rekeningen van justitie): These are administrative documents about the costs of the trial, imprisonment, and execution of the sentence. These can reveal details about Hendrik’s detention and any movements.

Population and Administrative Sources: Where Hendrik 'Lived'

To get a broader picture of Hendrik’s life, administrative archives are indispensable:

- Marriage and Baptism Registers: Although Hendrik only came to Hoorn later in life, you find his name in the marriage registers of Hoorn.

- Membership Books (Church): If he was a member of a religious denomination, his name might appear here. This provides insight into his religious background and possible social circles.

- Burgher Books/Citizenship Registers (Poorterboeken/Burgerschapsregisters): To work as a baker and start a business in Hoorn, the person must have acquired poorterschap (city citizenship). These registers can list his name, origin, date of registration, and sometimes his profession. This confirms his presence and (legal) status in the city.

- Guild Archives: Guilds kept registers of their members, apprentices, journeymen, and master tests. Here you can find names, registration dates, and any rules or fines.

Other Archives and Secondary Sources

- Notarial Archives: Think of wills, purchase deeds, or promissory notes. If someone owned property (like his bakery), incurred debts, or drew up a will, these documents can contain details about his possessions, financial situation, and relationships.

- Tax Registers: These can give an indication of his wealth and possessions, although they are often not detailed enough for a thorough personal reconstruction.

- Secondary Sources: Besides primary sources, which originate from the time itself, secondary sources (books and articles by other historians) are crucial.

- Historical Studies on the 18th Century: Books and articles on daily life, justice, economy, and migration in the Republic in the 18th century provide context and background information.

- City Histories of Hoorn: Specific works on the history of Hoorn can provide insight into the local situation and customs.

The Challenges of Historical Research and How the Author Handles Them

Historical research is rarely a ready-made process. Sources have inherent limitations that an author must contend with. If you do research yourself, you’ll encounter these pitfalls too:

- Fragmentary Nature: Sources are often incomplete. For ‘ordinary’ people like Hendrik, information is often limited to moments of official registration (birth, marriage, crime). The periods in between often remain a ‘black hole’. Here, the author fills these gaps with fiction.

- Subjectivity and Bias:

- Perspective of the Sources: Judicial archives are often compiled from the perspective of the authorities. They reflect their agenda, language, and interpretation of events. The voice of the accused is often only heard through their coerced confession or short answers to questions.

- Social Bias: Sources can be biased against certain social classes, genders, or nationalities. Migrants, for example, might be portrayed more negatively.

- Language: The language of the 18th century can differ from modern Dutch, with different nuances and meanings.

- Lack of Emotion and Inner Life: Historical sources, especially official ones, rarely provide insight into people’s emotions, thoughts, and inner motivations. They record facts and actions, not psychological complexity. This is the biggest challenge for an author of historical fiction.

- Transience: Many sources have simply not been preserved due to fires, wars, or disinterest.

- Errors and Inconsistencies: Even official documents can contain errors (e.g., incorrect dates, names, spelling) or inconsistencies between different sources.

The Author's Approach to Creating a Story

The author of “Uitgevlogen Ziel” deals with these limitations in the following ways:

- In-depth Research: As much relevant source material as possible has been studied to gain the most complete and accurate picture of the facts and historical context.

- Transparency: A good historical novel, like “Uitgevlogen Ziel,” often states in an afterword which facts are historical and where literary license has been taken. This helps you as a reader distinguish.

- ‘Educated Guessing’: Where sources are silent, the author must ‘guess’. These guesses, however, are ‘educated’; they fit within the logic of the time and the knowledge that is available. An 18th-century baker, for example, wouldn’t have had a mobile phone!

- Basing Assumptions on Context: If sources don’t describe Hendrik Baalman’s emotions, the author can draw on general knowledge of 18th-century human experience, or apply psychological insights to his (known) circumstances.

- Literary Fulfillment with Respect: The author fills in the gaps with dialogue, character development, and plot twists, but does so in a way that is respectful of the historical figures and events, especially when dealing with true crimes.

- Thematic Focus: Certain themes are emphasized that resonate with the available sources or that have universal meaning, and the fiction is built around these themes.

So, if you want to delve into historical research yourself, it’s essential to be critical, check your sources, and be aware of the gaps in history.